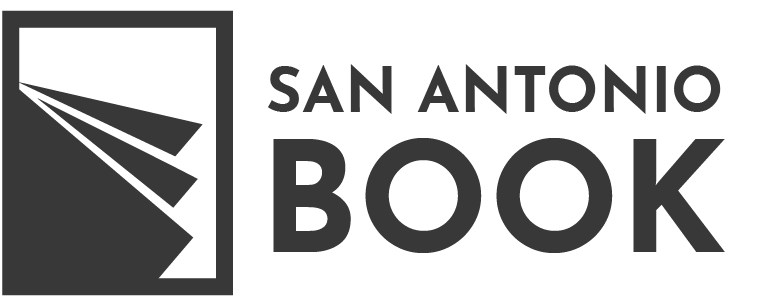

“Entire families, wiped out in the floodwaters, cry out from the pages of West Side Rising.” ― Huffington Post

“Miller chronicles how both before and after the storm, city leaders made a series of decisions that created the disparity in damage and death. The book shines when Miller expertly explains how the “natural” disasters that afflict Texas and other states aren’t really all that natural.” ―

Texas Observer

“Miller presents the case in such an irrefutable way that it is shocking. Even for those of us who feel that we have known the general sequence of events, the evidence is deeply painful because Miller lays it out with such clarity and power.”―

San Antonio Report

“Historian Char Miller writes that the flood exposed longstanding neglect of the city’s West Side but also laid the groundwork for a grassroots movement that eventually created major changes in the way the city operates.” ―

San Antonio Express-News

“Book tracks both the racist policies that affected recovery and how the city’s West Side showed its resilience.” ―

Texas Public Radio

“Not simply a story of raging floodwaters, West Side Rising tangles with environmental racism and makes time to fix names to the often marginalized and nameless victims of these overflows…a powerful story, a meaningful story.” – Kenna Archer, author of

Unruly Waters: A Social and Environmental History of the Brazos River,

“A good read is ahead, one that will make all manner of otherwise deadly material not just palatable but both enlightening and entertaining.”

Lewis Fisher, author of Maverick and Greetings From San Antonio

“Extreme weather, much of it exacerbated or even brought on by climate change, is the catalyst for many of the crucial issues Texas faces right now: hurricanes in Houston, drought in El Paso, the vanishing Edwards Aquifer, invasive species mucking up our waterways, and the current ERCOT advisories regarding energy curtailment. Many Texans look at these challenges and throw up their hands in despair. But Miller’s book offers an inspiring account of what can be achieved, at the local level at least, by motivated people with right on their side. ―

Texas Monthly

“Char Miller knows San Antonio―its people, its politics, its long and colorful history. In

West Side Rising, he trains his deep knowledge on a devastating downpour whose scouring floodwaters revealed―for those willing to look―decades of racism, environmental injustice, and policy-driven poverty. Thoroughly researched and gracefully written, West Side Rising is a close and intimate look at the Alamo City, to be sure, but it’s also an American story. It’s a cautionary tale, as climate crisis looms over us all.” ― Joe Holley, author of Hurricane Season: The Unforgettable Story of the 2017 Houston Astros and the Resilience of a City

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

The keys were a clue. Something was amiss. Still inserted in the front door of Ben Corbo’s popular fruit market at 422 Saint Mary’s Street, they attracted the attention of employees of the Hughes Auto Livery while they were in the process of clearing out their nearby shop in the horrific aftermath of the flood of September 1921 that tore through San Antonio, Texas. The flood had begun on the evening of Friday, September 9, with heavy rain lashing down over the San Antonio River watershed, and by 10 p.m. Saint Mary’s Street had become a river. Within two hours raging waters were crashing through downtown and devastating portions of the West Side neighborhood where the Corbo family lived. Some of the auto livery’s personnel, as they had headed home through the wind-whipped storm that evening, stopped by the fruit market to check on Corbo. He asked the men to escort his son to the family’s home on Monterey Street, one and a half miles west, while he remained “in the store a few minutes longer in an attempt to save some of the property.” Those minutes cost Corbo his life. But his death was not immediately known because the flood took out power and telecommunications for two days, and the city imposed a strict curfew that blocked access to the badly damaged downtown. It was not until Sunday morning, September 11, that some of the livery staff workers returned to inspect their shop. As they swung past Corbo’s shop, they spied his keys in the lock. Fearing the worst, the men sprang into action: “Hammering their way through the front of the building, rescuers attacked the wreckage . . . and after a search that continued into the middle of the afternoon the body was located beneath debris that filled the rear of the building.” In one sense, Ben Corbo’s death was preventable. Had he left the shop with his son he might have lived through that terrifying night; his family managed to survive. But then history is replete with what-ifs, questions that have no answers yet paradoxically point the way to some explanatory patterns. The fruit vendor, after all, was like many others who died in the most fatal flood in San Antonio’s history. Swirling with street pavers, automobiles, furniture, and branches, turbulent stormwaters undercut houses, commercial buildings, and bridges and killed many who lay asleep in their beds. Others, who had managed to escape their battered dwellings, were sucked into the maelstrom. Corbo was not alone in being trapped by relentless force of the water-borne debris. Yet his demise―he was one of an estimated eighty who succumbed that night―was unusual in this respect: only four people perished as a result of the San Antonio River’s floodwaters, and Corbo was the only adult. The other three were young children, pulled from their parents’ arms. The vast majority of those who perished were on the city’s densely populated West Side, in an area known locally as the corral or jacal district (so named for the huts and shacks many of its residents occupied). These rough shelters were no match for the powerful floodwaters that raced down the West Side’s interlacing of creeks―the Alazán, Martínez, Apache, and San Pedro. That evening, the Alazán, which curved one block west of Corbo’s home, proved the deadliest. This disparity in the demographics and distribution of death in San Antonio dovetails with a statewide pattern: spatial inequities, ethnic discrimination, and environmental injustices determined who survived and who died in this massive flood. “The total number of lives lost will never be known,” wrote U.S. Geological Survey water engineer C. E. Ellsworth in an extensive analysis of impact of the 1921 flood across central Texas, “but the best estimates available indicate that at least 224 people were drowned, most of whom were Mexicans who lived in poorly constructed houses, built along the low banks of the streams.” His careful qualification of the number of fatalities across the Lone Star State held true as well for San Antonio. “Undoubtedly many others were drowned and never reported missing. Many bodies were carried miles and buried in sand, mud, and debris along the river bottoms.” A particularly mournful example came to light one month after the flood. Several days before the storm, Mariano Escobedo, who lived with his wife, Maria, and two children in a shack on the banks of the Alazán near El Paso Street, had left town to find work in West Texas. It was some time before he heard about the flood, and even longer before he was able to scrape together enough money to return to San Antonio. “Persons in whom he applied for aid doubted his story and refused to help him,” so Escobedo saved “every penny he could” and gradually worked his way back to town. His small abode, which was located “in the path of the torrent that swept down Alazan Creek,” had vanished. Friends and acquaintances had no news of his family, and his dogged search for clues close to home and expanding downstream came up empty. The Red Cross, which “assisted him in every way possible,” had no record of Maria, Josephine M. Escobedo (age seven), or Jesus M. Escobedo (four months). The city police suspected that their bodies “may have been carried many miles away by the flood waters” and as a result probably would never be found. They also told the San Antonio Express that the disappearance of the three Escobedos was not unusual: “There were numbers of instances of persons in the Mexican district along the Alazan Creek washed away that were not brought to the attention of the Red Cross or other officials.” Those who perished in the floods that year―many of Mexican heritage, poor men and women whose manual labor was seasonal and low-paying and who therefore settled in the least expensive and most flood-prone terrain―were made all the more vulnerable because of the region’s geography, topography, and climate. The most devastated communities all hugged the Balcones Escarpment, a geological fault zone that runs for roughly 450 miles. Like a lopsided smile, it curves east and north from Del Rio on the Rio Grande all the way to the Red River delineating the Texas-Oklahoma border; it forms hilly contours that define San Antonio, New Braunfels, San Marcos, and Austin, and from Austin north to Georgetown and beyond. A modern signifier is Interstate 35, which parallels the escarpment to its east from San Antonio north. This rumpled and craggy landform is critical in several respects. It demarcates the southern terminus of the Great Plains, an elevated terrain that in Texas is known as the Edwards Plateau; some sections of the rough limestone and thin-soiled landscape are as high as two thousand feet or so. The land that slopes away from the fault line toward to the Gulf of Mexico is the southern coastal plain. The reciprocal relationship between these two masses and longstanding climatological patterns can produce wild swings in local weather. Because this region falls loosely within the transition zone between the humid eastern section of the United States and the arid west, the climate can toggle between deluge and drought, an oscillation fueled in part by whether an El Niño or La Niña system prevails. Another trigger mechanism involves the Gulf of Mexico. If its bathtub-warm, moisture-laden air pushes onshore, the flow will slowly lift with the rise in elevation. Once it reaches the escarpment the uplift is more abrupt, forcing the moist air to interact with colder temperatures above. The moisture condenses, the cooler air falls, then it is warmed and rises again, a cycle of convection that can result in major thunderstorms. “It has long been recognized,” notes C. Terrell Bartlett in a contemporary assessment of the 1921 flood, “that in many cases the sudden rise along the Balcones Escarpment causes intense precipitation along and just above its margin.” This intensity can generate blockbuster floods, a reality that has led the National Weather Service to dub San Antonio and the larger region along the escarpment “Flash-flood Alley.” Over the millennia, rains have carved a series of creeks, streams, and rivers into the limestone that widen as they reach the coastal plain and head to the Gulf, an erosive process that flooding could accelerate. In their more placid state, the San Antonio River, as well as the Guadalupe (New Braunfels), Comal (San Marcos) and Colorado (Austin) Rivers, have attracted and sustained generations of indigenous communities and in time Spanish, Mexican, and American settler-colonists. Each group took advantage of these systems’ life-sustaining properties and the ecological abundance that came from living within the fertile intersection of different biozones, prairie and plateau, grassland, riverine, and woodland. But should a furious thunderstorm explode over the upper reaches of the local watersheds, the floodwaters that sluiced down innumerable gullies and ravines and surged into streams could have devastating consequences. Within moments, the almost bone-dry San Antonio River and its arroyo-like tributaries could become churning torrents.